Summary :

A very complex geology

Limestone and dolomite to the west

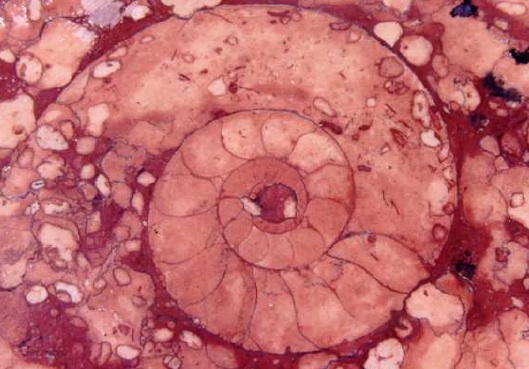

In the west of the Queyras there are sedimentary rocks - limestone like the pink marble of Guillestre, which contains fine ammonites, dolomite, marls and sandstone. These rocks have undergone the effects of the upthrust of the Alps in a recent geological past, with its folds and its piled-up sheets. Limestone and dolomite are clearly visible at Ceillac, where these rocks have formed the Fonsancte and the mountain of Assan, or near Arvieux at the Pic de Rochebrune. They form majestic and impassable cliffs (Combe and Gorge du Guil) and are responsible for the isolation of the Queyras from the rest of the department of the Hautes-Alpes, and the historic separation of Ceillac from the rest of the Queyras.

Dolomite and cargneule

Limestone is calcium carbonate, whereas dolomite is a carbonate with both calcium and magnesium, and in geological terms is much less soluble. Dolomite has formed some impressive cliffs, and peaks like those of Font Sancte above Ceillac. But it also makes for chaotic rocky landscapes of the kind you may see around Nîmes le Vieux or Montpelliers le Vieux in the Causses mountains. When limestone and dolomite are deposited together, for example at the bottom of a salt lagoon, the faster-dissolving dolomite (we are still talking in geological time-scales here) forms ‘cargneules’, porous pitted rocks like those which can be seen in the Queyras at Casse Déserte.

Glossy schists in the central Queyras

The central area of the Queyras is dominated by metamorphic rocks, notably schists. These are clays which have been ‘cooked’ at great terrestrial depths, with the result that they have lost all traces of fossils or earlier geological folds. Some Queyrassien people have taken schist slabs to cover their roofs.

Folded layers of schist could be formed only at extreme temperatures (400-500 degrees Centigrade), under extreme pressures, at extreme depths (3000 metres or more), where the rock became flexible and folded over without breaking.

The glossy schists that one finds in the Queyras are softer than limestone. They have not retained the marks of glaciers, and they formed the more open valleys one finds like that of Arvieux at the mouth of the Combe du Guil. Other examples are the valleys above Fort Queyras, from Château-Ville-Vielle to Ristolas on the way to Aiguilles-en-Queyras and Abriès, at Molines-en-Queyras and Saint-Véran. So geology explains the unity of the Queyrassien landscape and, in later times, of the history of its people.

Basalt and gabbro to the east

Lastly, to the east one can see crystalline rocks, termed ‘green’ rocks, such as the ophiolytes, gabbro, serpentines and basalt on the peaks above Abriès (Bric Bouchet) or Saint Véran (Mont Viso)

Among the pebbles of the river Guil at Ristolas one can find good samples of green serpentine.

Basalt pillows

IThese formations originated in deep oceans (about 3000m down) during volcanic eruptions. Boiling lava formed a crust on coming into contact with water and took the shape of a pillow which eventually burst under its own pressure, thus forming a new one.

These formations are very common at Le Chenaillet and Colle Verde near Montgenèvre (Hautes Alpes). There are some fine walks starting at Cervières for geology buffs.

Basalt pillows can also be seen at the Tête des Toilies above Saint-Véran.

Among sedimentary rocks, one can still find gypsum and cargneules, originally formed in salt lagoons. These rocks have created the remarkable landscape of Casse Déserte near Arvieux, on the Col d'Izoard road, with its stone towers, minarets and serrated outcrops, and the remarkable ravine of the Ruine Blanche at Montbardon (Château-Ville-Vieille).

It is geology that explains these distinctive landscapes.

The Alpine ocean in geological time

The Alpine ocean was a warm shallow sea containing corals (whose fossils can be seen in Massif de Rochebrune near Arvieux). At near-surface levels, ammonites swam (see the fossils in the pink marble quarry at Guillestre). In the lagoons gypsum was deposited - see the Ruine Blanche formation above the hamlet of Montbardon (Château-Ville-Vieille) – and cargneules (Casse Déserte near Arvieux). Fossilised sands, ribbed by the effect of waves, bear witness to an ancient beach. Clay and limestone deposits on the ocean floor were then transformed into schists by tectonic forces.

When the Alps were formed these sediments were carried up to a high altitude, and so today they are found alongside the basalt pillows which were originally formed 3000 metres under the sea. At Saint-Véran, in the high valley of Aigue Blanche, a fossilised scallop-shell has been found, abandoned on a strip of beach on the edge of the crystalline massif.

The effects of glaciers

There are many visible glacial effects: for example, the gorges of the river Guil, carved out by the glacier that flowed down towards the Durance and the foot of the Hautes-Alpes; the tight gorge of Château-Queyras with its two lateral notches, - both the road and the river are squeezed through here today; Pra Premier (a filled-in lake) on the track up to Clapeyto, and all the high mountain lakes and U-shaped valleys.

Glaciers have produced characteristic “sheepback” shapes as they’ve smoothed boulders in their path, and they’ve made sheer cliffs ideal for via ferrata.

Other forms of erosion

Mountain streams have filled the glacial valleys with their alluvium, flattening their bottoms, as in the case of the Guil above Château-Queyras and Ville-Vieille. Frost has shattered rock and produced countless casses (screes) at the foot of cliffs. Water itself has eroded rock directly: see the magnificent fairy chimney on the road to Molines-en-Queyras.

The geological museum of Château Queyras

If you’re interested in geology, visit the geological museum of Château-Ville-Vieille (Hautes Alpes).

Tel 04 92 45 06 23 or 04 92 46 80 46.Open from 10.30am to 12 and 3pm to 7pm from 1 July to 31 August or by arrangement