Copper mine

The Clausis copper mine at Saint-Véran

Saint-Véran in the Queyras (Hautes-Alpes) is the village where "the rooster pecks at the stars". At 2042 m, it is the highest commune in Europe. Up there in the mountains, in the land of marmots and chamois, at an altitude of 2,400 m, near the Clausis chapel, you can still see the remains of a copper mine.

4400 years of history

It's the end of the third millennium BC. Already, the Stone Age is drawing to a close, the Chalcolithic, the age of stone and copper, is underway, and the Bronze Age is about to take off.

Copper was used to make jewelry, cooking utensils, tools and, of course, weapons. The addition of tin to copper soon made it possible to harden not only tools, but also weapons, giving warriors with shields, armor and spears of bronze a distinct advantage.

How did the men of the time discover the vein? How did they exploit it with their stone tools? Where did they get the knowledge they needed to obtain the coveted metal? Where did they live while they worked?

These are difficult questions to answer.

What archaeologists do know is that the round marks that a trained eye can detect on certain rocks are the mark of their homes.

Roman times

The Romans knew about the Saint-Véran copper mine. The coin of Antoninus the Pious (Roman emperor 138-161 A.D.), found at the entrance to a gallery, bears witness to this.

As the prehistoric outcrop was exhausted, increasingly lower galleries had to be dug to reach the vein, which sinks almost vertically into the ground.

You can imagine how hard this work was in the mountains, at an altitude of 2,400 m, in the cold, snow and ice, especially at the beginning and end of the season, and how difficult it was to transport the ore down to the valley, probably on human back, or perhaps by mule.

We also wonder about the living conditions of the workers.

Were they recruited locally? What was the importance of the village that would one day become Saint-Véran? Was the workforce imported?

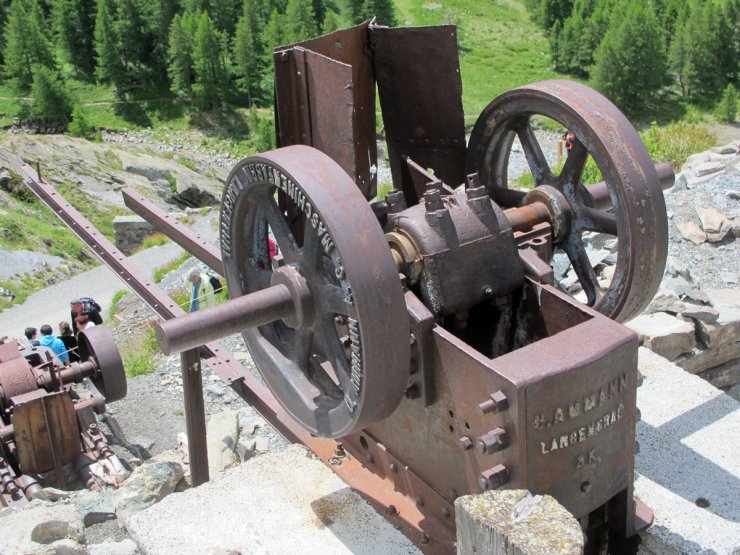

Mechanization in the 20th century

In 1901, efforts were made to adopt modern mining techniques, including blasting, transporting waste rock and ore by railcar, and crushing and washing the ore.

The access tunnels became longer, as the veins had to be dug deeper and deeper. The ore extracted was not processed on site, but shipped to metallurgical sites such as the Vedène smelter in Vaucluse or Swansea in South Wales.

In 1957, the torrential rains that had caused so much flooding and destruction in the Queyras region triggered landslides that sent a large part of the mining equipment to the bottom of the valley.

This was followed by an accident in which two workers were killed, and then by an explosion that seriously damaged the machine room.

The investment required to bring the Clausis mine back into operation was too high. The mine was closed in 1961.

Complex metallurgy

In ancient times, copper could be found in its native state, i.e. as an almost pure metal. This is presumably the form in which it was discovered at Saint-Véran at the end of the Stone Age.

Samples of native copper were found by 20th-century miners.

Most often, however, copper comes in the form of ore, copper sulfide mixed with iron and other metals such as gold, silver and platinum, and embedded in a stony gangue.

At Saint Véran, the ore, bornite (copper-iron sulphide CU5FeS4), is scarce but surprisingly rich in copper, close to 40%, whereas in Chile, where it is mined in huge open-pit mines, the ore contains only around 3%.

To extract copper, the ore must first be separated from its gangue. This is done by sieving, crushing, grinding and sorting. This produces a coarse powder, which is then washed and decanted to obtain an ore concentrate.

It's likely that this was the end of processing at Saint-Véran in the Bronze Age, as very few traces of copper extraction furnaces have been found.

To separate the copper from the iron contained in bornite, the concentrate obtained must be heated to 1300°C, with the addition of silica to form a slag with the iron that is easy to remove. Achieving such a high temperature was the challenge faced by Stone Age mankind. They succeeded in building efficient smelting furnaces activated by bellows and tuyères.

Such tuyères have been found at Chapelle de Clausis, a stone's throw from the mine... but archaeologists have yet to discover the process used by the ancients.

Two discovery trails

We can't recommend an excursion to the copper mine enough for children, who will enjoy following in the footsteps of the miners. The site is magnificent, and the visit instructive.

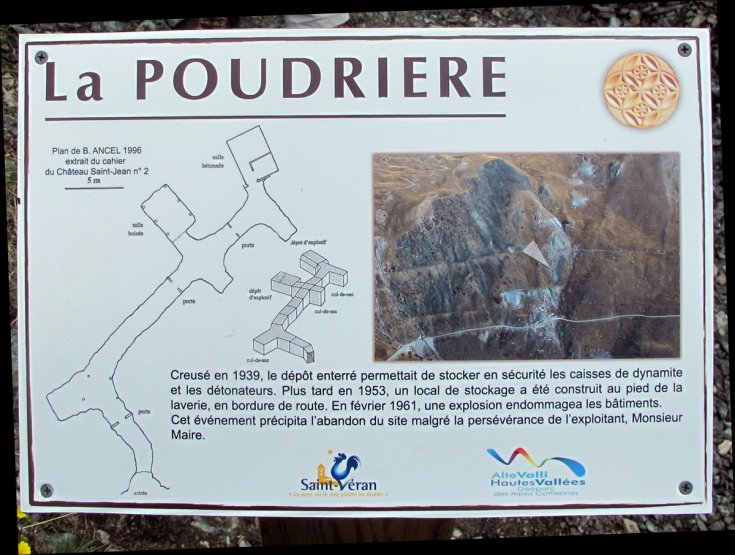

A day trip starting from the village of Saint-Véran (Fontaine du Chatelet): approx. 5h round trip with no difficulties. After following the old irrigation canal (Grand Canal), you'll come to the site of prehistoric mining (the "Ancients' Trench") by climbing up the Pic de Châteaurenard road; you can then descend to the remains of modern mining to discover the powder magazine, the gallery entrances, the laundry..

Well-documented panels provide the information you need to fully understand the site.

- A 30-minute tour from the marble quarry, accessed via the route de Clausis (shuttle bus in summer), takes in the remains of the modern quarry. The walk back to the village takes around 1h15.

To find out more, watch the video"Un trésor caché dans la montagne" ("A hidden treasure in the mountains") by the Parc Naturel Régional du Queyras on Vimeo.