Summary:

- Wood-carving

- Pottery

- The birth of pottery

- The marriage of water and clay

- The potter’s wheel

- The foot-powered wheel

- The decoration phase

- Inlays and glazes

- The firing phase

- Tant va la cruche à l'eau... (old French proverb « you can take the pitcher to the water once too often »

- Learn lace-making

Wood-carving, a Queyras tradition

From tree to log

To begin with, there are two trees very common in the Queyras: the larch, said to be rot-resistant, and the Swiss stone pine, whose wood is soft and easy to carve. Craftsmen of the past would make ‘fustes’, log-piles of squared-off larch timber which allowed the passage of air for drying hay in Queyras lofts. Nowadays, craft furniture-makers use stone pine in their work.

Swiss Stone Pine (pinus cembra)

The Swiss Stone Pine (French: pin cembro) is a tree of the high mountains which grows at altitudes of 1700-2400m, where winters are long and hard. It is common in the Hautes-Alpes and the Queyras, particularly in Abriès, Molines and Ristolas. Its needles form in bundles of five. Their cones don’t release their seeds until a year after they have fallen. The spotted woodpecker is very fond of the seeds and stores them in hidey-holes whose location it subsequently forgets – thus contributing to the spread of the Swiss stone pine.

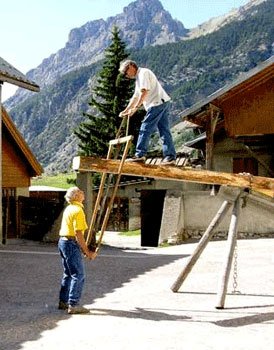

From log to plank

Les troncs pouvaient être utilisés bruts par l'artisan charpentier pour certains travaux comme la construction de fontaines et d'abreuvoirs, mais le plus souvent il fallait les équarrir pour confectionner les fustes ou les débiter en planches. On utilisait alors la loube qui était manoeuvrée par deux scieurs de long comme à la fête des traditions de Ceillac : l'artisan du haut remontait la lame qui avec son cadre était assez lourde ; celui-du bas la descendait en sciant. L'ensemble nécessitait une excellente coordination et une grande précision dans les gestes pour ne pas dévier et obtenir des planches d'épaisseur régulière.

The role of the blacksmith

Certain jobs require the help of a blacksmith, for example when making the basin for a fountain. The planks are carefully fitted together to make them watertight, then an iron clamp is added to increase their resistance to water-pressure.

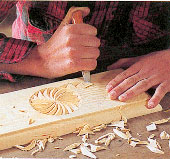

Carving with a knife

Folk art in wood in the Queyras typically consists of carving inlaid rosettes on furniture and various household objects such as salt-pots, butter-dishes and different sorts of boxes. These compass-drawn motifs are repeated and overlaid in thousands of ways. Holiday-flats often contain this traditional carved furniture..

Some craftsmen prefer to work in relief, which requires them to carve several centimetres into the surface of the wood. In this case they use gouges which leave characteristic rounded marks. Designs vary widely. Stone pine is a light-coloured wood, so after the carving is complete a walnut stain and a little wax are added to give a warm-coloured finish.

The Co-operative Craft Shop (La maison de l'artisanat) in Château-Ville-Vieille

Of course we’re not expecting you to take away planks or drinking-fountains as souvenirs of your holidays in the Queyras!

But you might be interested in a table, a sideboard or a chest. Or maybe you’re just interested in folk art and you want to see typical Queyrassin furniture.

A visit to the the Maison de l'Artisanat in Château-Ville-Vieille (Hautes-Alpes) will help you decide. (Open every day.Telephone 04 92 46 80 29.)

POTTERY

The birth of pottery

Early humans needed something to keep their food clean of dust and mud. Their own houses of wattle-and-daub must have suggested to them other uses for the clay they found at the edge of streams, a clay which dried hard and brittle in the sun. So the idea of pottery was born. With earth, water and fire useful containers could be fashioned. Over time, techniques became more refined and smoother bowls, plates, vases and jars were made. Eventually potters invented the turntable to create regular shapes from the clay, and their imaginations showed them how to make use of them.

The marriage of water and clay

Clay is easily found; it dries to a hard substance, but once this is wetted it becomes malleable. Mixed with a little straw, it can make crude bricks which will dry and harden in the sun. Potters, however, know they have to do more, producing a flexible paste which requires lengthy kneading to get an even texture and remove the air-bubbles which would burst at the firing stage and ruin the pot. After that, the mixture must be left to lie for a long time. If it turns out too stiff, the potter will have to add more water, and if it’s too soft he will have to wait longer again for it to dry out. At the right point, he will divide the clay into lumps of different sizes for the different objects he plans to fashion from it.

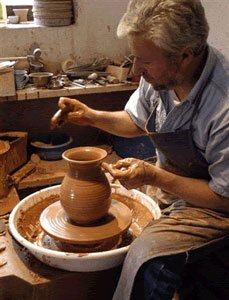

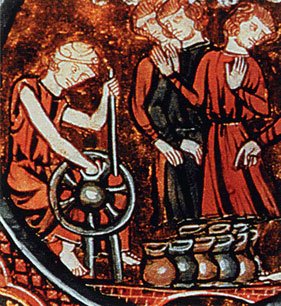

The potter’s wheel

This tool has a long history. Its purpose is to turn the chosen piece of clay in order to achieve a regular shape. Its design is simple: a vertical shaft set in a frame, with a heavy stone flywheel at the bottom and a spinning plate on top, onto which the potter throws the clay. The power to make the spinning action has changed over time. Medieval potters used a stick to turn the spokes of a second wheel which was linked to the main wheel. This would keep the rotation going for a few minutes while the potter worked the clay on the turntable, but every so often he had to break off in order to set it going again.

Foot-operated wheels

The invention of the foot-operated potter’s wheel enabled the potter to adapt the speed of rotation to the different phases of modelling the clay. Some wheels had pedals like our grandmothers’ sewing-machines. Nowadays they are powered by electric motors with variable speeds, freeing the workman completely from the task of providing the motive force for his wheel himself. The knack then is to literally throw the clay onto the fast-spinning turntable - aiming to hit the exact centre, because there is no chance of pulling the clay off again once the wheel is spinning.

In the next phase, the potter slows the wheel and gradually hollows out the revolving lump of clay with his thumbs, raising the sides of the cylinder until he can shape it into the piece he wants; this is where the substance comes alive and the potter becomes an artist.

When the piece is ready, the potter puts it aside to set. If a handle is required, this must be made separately and, once hardened, can be attached to the vessel with a ceramic glue or ‘slip’, a thin clayey preparation which will harden during the firing process.

Decoration

The craftsman potter decorates his piece with different designs: regular incisions with a specialised tool; raised motifs using pieces separately prepared, often in moulds, and then glued on with slip; glazes and enamels soaked into the clay or painted on.

Glazes and enamels

Glazes are thin mixtures of clay which have been sifted to remove grit and lumps. The material they are made of will produce various colours, ranging from beige to brown, after firing. Enamels are a mixture of crushed stone, various ashes (pine, oak, lavender, vine-stock) and water-based oxides. Ash consists of silica (once used for scouring pans) and different mineral salts like potash. In the firing process the ash vitrifies and the salts add colour. Metal salts can also be added: iron for brown, chrome for green, cobalt for blue, vanadium for yellow and gold powder for red.

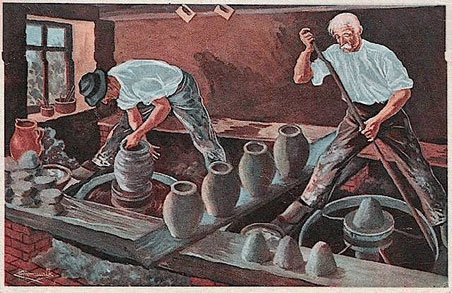

Firing

Once a piece has hardened sufficiently in the air, it is placed in an oven and heated in stages to a temperature between 700 and 1200 degrees Centigrade. A viewing-window allows the potter to monitor the progress of the firing and intervene if it appears to be going too slowly or too fast. Here too electricity has replaced the traditional wood or charcoal for heating, making temperature- control easier. If the heating is overdone, the piece will break. If it still contains air-bubbles, these will expand and destroy it. But if all goes well, the clay will become as hard as stone. At a lower temperature (though still 700 degrees) the product will be porous and sensitive to cold. So where the retention of liquids is desired, clay which naturally contains silica (1) or has it added, will be used, and heated up to 1200 degrees. Then the silica vitrifies and produces totally waterproof earthenware.. At these temperatures enamels also vitrify and produce lively colours.

(1) There is an exception to this, namely ‘guggleware’ (in French gargoulette, in Spanish alcarazas). These are porous earthenware pots which will sweat and keep their liquid contents cool. ‘Tant va la cruche à l’eau qu’à force elle se brise’,

In French we say,

Tant va la cruche à l’eau qu’à force elle se brise…

roughly meaning ‘If a pot holds water long enough it will wash away’, or everything and everyone has a limited life..

Archaeologists love to classify and inventory pottery artefacts which enable them to date when their sites were occupied.. In ancient tombs they often dig up intact jars of offerings. If they come across the middens in some ancient inhabitation, they may well find whole broken vases, often beautiful and remarkably well preserved, which have been discarded by servants anxious to conceal their loss from their mistresses

An old potter’s workshop in the hamlet of Le Coin, near Arvieux

Bernard and Geneviève Blanc, local potters, have been making decorative and household pottery in stoneware, porcelain and glazed earth for years.

If you are staying with them you will be able to learn the skill of pottery. In an informal atmosphere (no training, no lessons) you can play at being a potter by working the wheel and decorating your own creations.

Geneviève et Bernard BLANC

Tél : 04 92 46 75 73

gegebernard05@gmail.com

Learn lace-making with a lace-maker

Mireille LAFFONT- Dentellière - 06 69 50 58 61

In Arvieux (Hautes-Alpes), in a relaxed atmosphere, I will show you the art of lace-making with bobbin and pillow. Men and women, or children over 8, will be taken though every detail of this skill. Each session lasts two to three hours. Open all year. I supply the lace material and you get to take your work home.

I learnt how to make Queyras lace with Jean-Paul Farfantoli and I have studied for several years in the lace-making studio of Le Puy.

Cost: 7 euros per hour. Group reductions and subscriptions available. Special prices for regular clients.

f on the other hand you think you don’t have the necessary skill to do it yourself, come to my travelling lace-exhibitions where I’ll show you lace-making techniques, caps and dresses, and give demonstrations of lace-making on pillow and frame.

If you’re interested in lace and the clothes and life-style of yesteryear, visit the Maison du costume in Abriès and the Musée du Soum in Saint-Véran. You won’t be disappointed.