Queyras craftsmanship

Woodworking, a Queyras tradition

Craftsmanship, from tree to chestnut

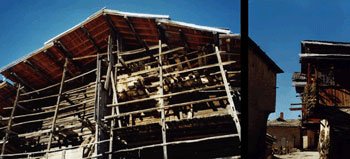

In the beginning, there were two trees, quite common in the Queyras and Hautes Alpes regions: the larch, reputed to be rot-proof, and the cembro pine, whose wood is soft and easy to work.

It was with larch that the craftsmen of yesteryear builtthe fustes, stacks of squared trunks that let air through to allow hay to dry in the granaries.

Furniture craftsmen like to use cembro pine, which is easy to carve.

Cembro pine

The cembro or arolle pine is a high-mountain tree that thrives at altitudes of between 1700 and 2400 m, where winters are long and harsh.

It is abundant in the Hautes Alpes and Queyras regions, particularly in Abriès, Molines and Ristolas.

Its needles are grouped in fives. Its cones only open to release their pinions a year after they have fallen to the ground.

The speckled nutcracker, a great fan of these pine nuts, piles them up in hiding places and sometimes forgets where they are, helping to spread the arolle.

From trunk to board

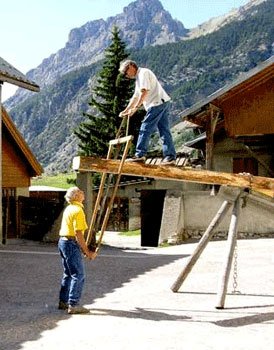

Trunks could be used in the rough by carpenters to build fountains and drinking troughs, but more often than not, they had to be squared to make trunks or cut into planks.

In such cases, the ladle was operated by two pit-sawyers, as was the case at Ceillac's traditional festival: the craftsman at the top raised the blade, which with its frame was quite heavy, while the craftsman at the bottom lowered it while sawing.

The whole operation required excellent coordination and precision of movement to ensure that the planks were of even thickness.

When the blacksmith gets involved

The blacksmith was called in for certain jobs, such as the construction of this fountain tub.

The boards are carefully adjusted to ensure a watertight seal.

Iron strapping helps them withstand the pressure of water.

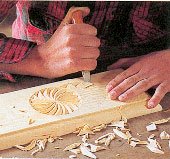

Knife carving in the Queyras

Queyras craftsmanship is characterized by intaglio rosettes carved with knives on furniture and other everyday objects such as salt shakers, butter dishes and boxes.

The compass-carved motifs can be repeated and intertwined in a thousand different ways.

This type of carved furniture is often found in rental apartments.

Some craftsmen prefer relief carving , which involves lowering the surface of the board by a few centimetres.

The work is done with a gouge that leaves its characteristic mark on the wood. The motifs can be very different.

Cembro pine is a light-colored wood. After finishing, it is stained with walnut stain and a little wax to give it its much-appreciated warm color.

The craft house at Château-Ville-Vieille

Of course, we're not suggesting you take home a trough or a drinking trough as a souvenir of your vacation in the Queyras.

But perhaps you need a piece of furniture, a table, a sideboard or a chest? Or are you simply interested in craftsmanship and curious to take a closer look at Queyrassin furniture?

A visit to the Maison de l'Artisanat in Château-Ville-Vieille (Hautes Alpes) is a must.

(open daily - tel: 04 92 46 80 29 )

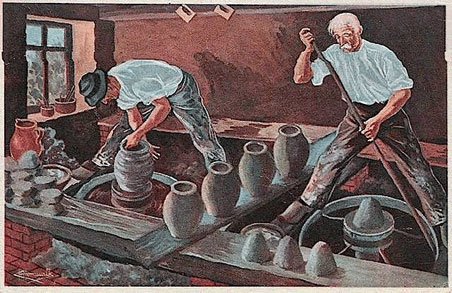

A pottery workshop in the Queyras

The birth of pottery

Sitting in front of his cave, a man from the depths of time meditates. He could do with something to put his food on as it lay there in the dust.

Admittedly, he's not a delicate man, he's always been that way, but there are the little ones... He thinks of his home, which he fashioned from the slippery earth he found on the banks of the stream. When it came into contact with the flame, the earth became hard and brittle

... Already in his mind, pottery is born. With earth, water and fire , he created the bowls he needed.

Little by little, his technique was refined. Rough bowls are hollowed out and becomebowls, dishes, vases, jars..

In the meantime, he had invented the lathe , which enabled him to obtain regular shapes, and the muses with whom he populated his universe taught him the art of using it.

The marriage of earth and water

You don't have to go far to find earth.

Any clay you can find within walking distance will do. It's hard when it's dry, but all you have to do is wet it a little and it becomes malleable.

Mix it with a little straw and you've got raw bricks that will harden in the sun.

The potter knows he has to go further. He must make a supple dough , kneading it for a long time to make it homogeneous and eliminate the air bubbles that would cause it to burst during firing. Before using it, he must let it rest for a long time. If it's too hard to work with, you'll need to add more water. If, on the other hand, it's too soft, he has to wait for it to dry out a little.

He then carefully prepares his clods of different sizes, from which he will make a wide variety of objects.

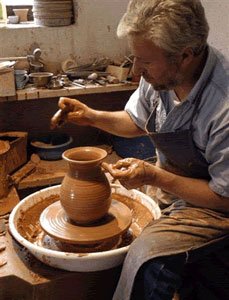

The potter's wheel

It's a very old one. Its purpose? To rotate the piece in preparation to give it a regular shape.

The principle is simple: a shaft held vertically in a frame, a stone disk of varying weight at one end to act as a flywheel, a plate called a girelle on the other to hold the clay, and a system to make the whole thing turn. Solutions have evolved over time.

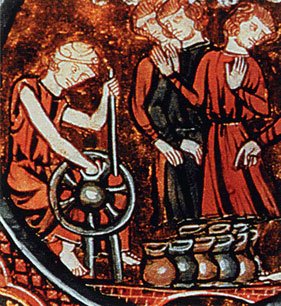

In the Middle Ages, the stick lathe was used, with the stick pushing on the spokes of a wheel linked to the lathe. The wheel would spin for a few minutes, but soon the potter had to stop and restart it.

The foot-operated wheel

The invention of the foot-operated wheel enabled the potter toadjust the speed of rotation to the different phases of his work. Some were equipped with pedals, like grandma's sewing machines.

Today's lathes are equipped with an electric motor and variable speed drive, which frees the potter from having to supply the energy himself.

The lump of clay is placed on the girlle of the high-speed wheel. It must be precisely centered. As there are no marks on the wheel, the task requires all the craftsman's skill.

He then reduces the speed, and with his thumbs creates a slot in the clod, which he widens and works to hollow out the piece and raise its edges, shaping it to his needs and tastes. This is where the material comes alive and the craftsman becomes an artist.

When the piece is ready, he sets it aside to harden. Does it need a handle? He sets it aside, and when it too has hardened, he glues it in place with barbotine, a very fluid clay preparation that hardens in the fire.

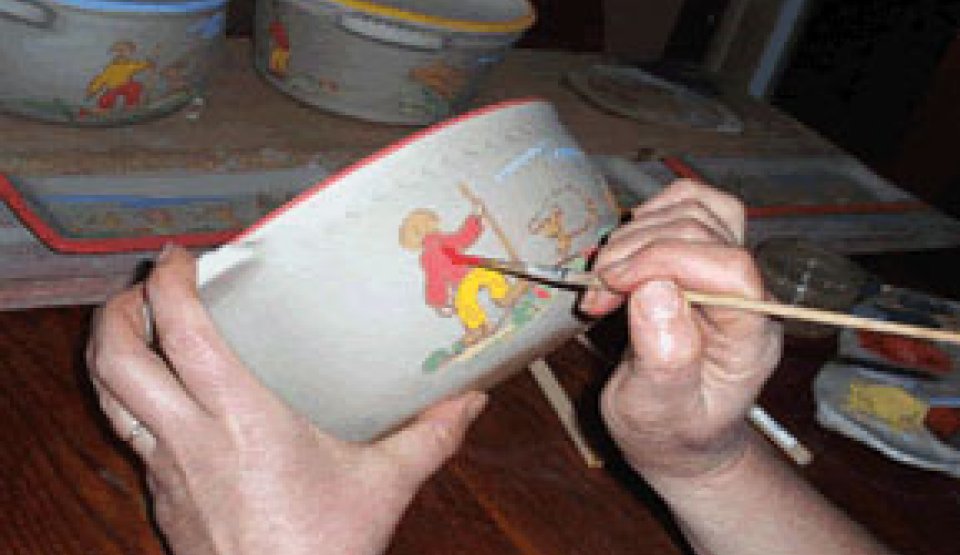

Decoration

The artisan potter decorates his piece with a variety of motifs: regular incisions with a suitable tool, relief motifs prepared separately, often in molds, and glued with slip, engobes and glazes applied by dipping or brushing.

Engobes and glazes

Engobes are clay slurries sieved to remove debris and lumps. Depending on their composition, they produce firing tones ranging from beige to brown.

Enamels are a mixture of crushed rock, various types of ash (pine, oak, lavender, vine, etc.) and oxides suspended in water.

The ash is made up of silica (used for scouring pots) and various mineral salts such as potash.

On firing, the silica vitrifies, while the mineral salts provide the color.

Metallic salts can be added: iron for brown, chromium for green, cobalt for blue, vanadium for yellow and gold powder for red...

The fire

This is the moment of firing. The piece, which has hardened sufficiently, is placed in the kiln and heated in stages to a temperature that can vary from 700 to 1200 degrees.

A window allows the artisan potter to monitor the firing and intervene if it is too fast or too slow.

Here again, the electric kiln has replaced the wood- or coal-fired kiln , making it easier to control temperature. If the piece is heated too brutally, it will break. If it still contains air bubbles, these will expand and cause it to explode.

But if all goes well, the clay will become as hard as stone. At low temperatures (700 degrees- it's all relative!) we obtain earthenware, which is porous and sensitive to frost. To preserve liquids, we prefer to use silica(1) loaded clays, either naturally or by addition, fired at 1200 degrees.

The silica vitrifies, making the stoneware totally impermeable. At these temperatures, the glazes also vitrify, giving them astonishingly vivid colors.

(1) The gargoulette, also known as alcarazas, is a notable exception. It's a porous terracotta vessel that transpires to keep the water in it cool.

It's a case of the pot calling the kettle black..

Archaeologists are very fond of pottery , which they have duly classified and catalogued, enabling them to date the occupation of their sites. In tombs, they often find intact jars of offerings, but if they come across a home's lavatory, they may find complete broken vases, often very beautiful and remarkably well preserved, thrown there to hide their loss from the mistress of the house.

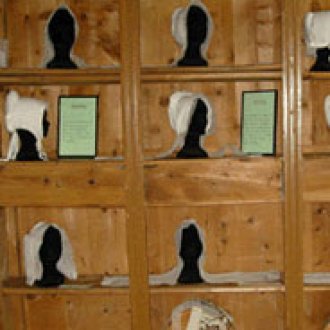

Are you interested in lace and want to know more about clothing and life in the past? Visit the Maison du costume in Abriès and the Musée du Soum in Saint-Véran. You won't be disappointed.